The long-lasting Iberian rivalry was one of the most enduring legacies of South America colonization. The wave of independence movements that hit this region in the first decades of the 19th century was not enough for national political and economic elites to overcome the antagonisms of the colonial period. This political dissent caused not only diplomatic withdrawal, but also serious conflicts between the newly independent countries (DORATIOTO, 2002), such as the War of the Triple Alliance between 1864 and 1870, when Argentina, Brazil and Uruguay fought against Paraguay.

As armed disputes cooled, South American countries (SAC) began to seek greater international projection through trade agendas based on the export of agricultural and mineral products and the import of manufactured goods (CERVO, 2015). This trade model, however, caused recurrent deficits in the payments balance of SAC with growing external indebtedness, as well as economic and trade dependence on European countries and the United States. In different periods of the 20th century, some SAC, such as Brazil, Peru and Venezuela, sought to develop domestic industrialization as a strategy to reduce the importation and surpass this structural trade imbalance.

The combination of exporting basic products to developed countries and creating domestic industries strengthened the low degree of trade integration between SAC. In the second half of the 20th century, sub-regional integration initiatives mitigated the scarce trade relations between these countries. Through Latin American Integration Association (ALADI), the Andean Community and Southern Common Market (Mercosur), SAC intensified trade flows not only among themselves, but also with other parts of the world. After 1990, under the aegis of liberal economic and trade postulates, SAC opted for the adoption of open regionalism as a way to improve their global economic insertion (VEIGA; RIOS, 2007), since the globalization of markets and the creation of global value chains became the new vectors of development (WEGNER, 2018).

The deepening of regional trade relations contrasted with the lack of political convergence between SAC leaders. This mismatch between trade integration and political cooperation began its change in 2000, when First Summit Meeting of the South American Presidents took place in Brasília, the capital of Brazil. This event became a milestone in the process of seeking regional integration, as it was the first time that political leaders from these countries met without the presence of an extra-regional power (IIRSA, 2000).

The regional leaders agreed that the development and greater global projection of SAC would undergo greater political, diplomatic and strategic densification. In this context, the trade and economic gains derived from open regionalism proved to be insufficient. SAC failed to achieve robust economic growth rates, while the region’s share of world trade flows declined slightly. Consequently, the search of joint political reorientation paved the way for the creation of the first international organization that would have the participation of all SAC: the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR) (US, 2000).

The present research seeks to analyse the geopolitical events that developed and, gradually, undermined South American cooperation. Through qualitative research, primary [official documents] and secondary [specialized bibliography and technical reports] sources were used for a descriptive analysis of cooperation in South America. In this way, the South American integration process was analyzed through overlapping initiatives of state and non-state actors at three different scales: internal; regional; and global. Finally, the research seeks to build a scenario for the difficult resumption of regional integration.

The late cooperation

The First Summit Meeting of the South American Presidents took place during a regional situation marked by trade and economic difficulties, Due to the existence of recurrent deficits in the balance of payments in addition to the economic stagnation. SAC were vulnerable to the recurrent economic crises that afflicted several countries, such as Mexico, Thailand and Russia. In a context of economic difficulties and the search for greater trade competitiveness, foreign investments destined for SAC became scarce, which pressured governments to present a political alternative to overcome the effects of “asymmetric globalization” (COSTA; GONZÁLEZ, 2014).

Consequently, in 2000 national leaders proposed regional cooperation initiatives that prioritize sustainable development, reducing sub-regional socioeconomic asymmetries, and increasing productive and economic interdependence among SAC. Based on the Communique of Brasilia, the Heads of States ratified their commitment to regional coalition and created Initiative for the Integration of the Regional Infrastructure of South America (IIRSA). This initiative stemmed from the recognition that South America had precarious infrastructure networks, which represents an obstacle to the process of trade integration and economic development, thus it aimed to promote development of those networks.

Based on an integrated vision of transport, energy, and communications infrastructure, the representatives of the South American States built a portfolio of projects compatible with the political, social and geo-economic context of each of the Integration and Development Axes (SENNES, 2010). As IIRSA projects advanced and other Summit Meeting of the South American Presidents followed, regional cooperation began to show greater institutionalization. Through Cusco Declaration (IIRSA, 2004), the South American Community of Nations was created, based on eight objectives: to improve political dialogue; expand physical integration; defend the environment; promote energy integration; create South American financial mechanisms; reduce regional asymmetries; promote social cohesion; and integrate telecommunications networks. It seemed that the path that would lead the South American peoples to integration was definitely being followed.

In a context marked by the predominance of political leaders linked to different spectrums of the political left (the “Pink Tide”), these leaders concluded a consensual statute during the 2008 Summit Meeting of the South American Presidents, in Brasilia, Brazil. The UNASUR Constitutive Treaty was signed at this event, strengthening regional integration through the primacy of planning and joint decisions. In addition to a general secretariat, councils were created for specific subjects. Among them, the South American Council of Infrastructure and Planning COSIPLAN), the South American Council of Health and the South American Council of Defense (CDS) stand out. Thanks to this political consolidation and joint strategic planning, South America became a geopolitical region (COSTA, 2009). The beginning of the 2010’s decade represented the institutional pinnacle of UNASUR.

The political and institutional mismatch

Until the creation of COSIPLAN in 2008, IIRSA projects were strongly influenced by the principles of open regionalism. This primacy made it difficult to form regional value chains. One of the main positive externalities derived from the construction of regional infrastructure networks is the fluidity of goods, capital and labor force. For this reason, IIRSA’s project portfolio would encourage both this fluidity of production factors and the formation of production chains between SAC, which would be an embryo of regional productive integration. However, the regional strategy of improving export corridors caused two aggravating effects on the troubled economic context that the region was going through at the end of the 2000s.

The first effect was the scarce formation of regional value chains and a low degree of expansion of industrial production. At the same time that SAC sought regional cooperation, they signed free trade agreements through ALADI. This resulted in the creation of a free trade area in South America. These initiatives favored an increase in exports of manufactured goods in Brazil, which resulted in an increase in the country’s trade surplus with almost all SAC.

The second effect was the disarticulation of trade between SAC. As their economic growth rates fell, the authorities in each country began to look for alternatives of improving their own exportations. In 2012, Chile, Peru and Colombia joined Mexico to create the Pacific Alliance (DURÁN LIMA e CRACAU, 2016), in order to expand trade integration with each other and with other regions of the world, especially the Pacific basin. Colombia and Peru also signed free trade agreements with the US. Argentina, in order to reduce the trade deficit with Brazil, started to limit non-automatic import licenses for the entry of goods produced in this neighboring country. These initiatives caused a decrease in intraregional trade, which allowed China and the US to expand their trade share.

The effects of the global economic crisis, institutional fragility and trade differences between countries made regional cooperation a non-priority objective. In the wake of these problems, UNASUR started to be mistakenly identified as the origin of the current socioeconomic problems by critics and the most conservative political groups of SAC. Furthermore, Brazil, one of the main sponsors of the search for regional integration, was experiencing strong domestic political instability. The Dilma Rousseff government faced recurrent public protests due to low economic growth, inefficiency of integration cooperation, accusations of corruption, rising inflation and currency devaluation. As a result, after 2013, Brazilian diplomacy diminish the participation in UNASUR activities.

In 2014, the Venezuelan social, political and economic crisis worsened. Through a troika of ministers of foreign affairs of Brazil, Colombia and Ecuador, Brazil joined an electoral supervision mission under the aegis of UNASUR. This mission sought both to mitigate the harmful effects of this crisis and to propose alternatives to safeguard political and democratic institutions of Venezuela. Despite the crisis worsening, Brazilian participation in relation not only to these problems, but also to other UNASUR agendas, was scarce or non-existent in 2015 and 2016. Michel Temer’s ascension to the presidency of Brazil in 2016 initiated a foreign policy based, among other characteristics, on criticism of the objectives and functionality of UNASUR. In this way, Brazilian diplomacy distanced itself from almost all regional themes, which provided space for action for other countries. Political initiatives derived from the fragmentation of regional governance emerged in the wake of this process: the Lima Group and the Forum for Progress and Development in South America (PROSUR Forum).

The influence of extra-regional powers in South America

South America is going through a process of economic-trade disintegration and political fragmentation. The sinking of intra-regional flows of production, the growing trade dependence on extra-regional countries and the replacement of UNASUR by institutional arrangements of partial scope derived from transformations that have taken place both in the international sphere and in the domestic one of SAC. The COVID-19 pandemic aggravated this context (BARROS, 2020).

The international system has demonstrated the intensification of trade and geopolitical disputes between the great powers. In the last few years, the US, the EU, China and Russia have sought to strengthen ties with their traditional allies and expand their influence in some strategic regions. South America is part of this process. These powerhouse States have expanded their trade, political and strategic ties with SAC, which has weakened the resumption of a joint project of international projection.

Since the end of World War II, the US has been the hegemonic actor in South America. Whether because of the 1947 Inter-American Treaty of Reciprocal Assistance, or the creation of the Organization of American States in 1948. Besides the attempt to implement the Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA) between the 1990s and 2000, the US has designed and attempted to expand its power on that subcontinent (PECEQUILO; CARMO, 2015). Since the FTAA proposal did not obtain the consent of Latin American countries, the US began to establish bilateral free trade agreements. In South America, these agreements were signed with Chile (2005), Colombia (2006) and Peru (2009). There are ongoing negotiations with the Ecuadorian government to sign a preliminary free trade agreement. These agreements have undermined intraregional trade as the SAC have replaced regional suppliers of industrialized goods with US manufacturers.

Moreover, Colombia’s accession as a NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organization) partner in 2017 (NATO, 2021), with decisive support from Washington, and the elevation of the bilateral relationship with Brazil to the status of important extra-NATO ally in 2019, negatively affected the military and geopolitical balance of South America (US, 2019), since political pressures against Venezuela have increased. These military partnerships replaced the cooperation in the field of security and defense that was built at the CDS during the existence of UNASUR. Thus, SAC returned to the individual planning of their military strategies, as well as to the search for partnerships with extra-regional powers for the supply of military technology.

The EU has sought to strengthen bilateral relations with SAC by holding two summits with CELAC in 2017 and 2018 (EU, 2020). Furthermore, it helped strengthen bi-regional cooperation, addressing topics, such as international peace and security, trade, environment, and exchange in science and technology. The EU and Mercosur concluded the negotiation of a trade deal in 2019 (Ibidem, 2020b). It will constitute one of the largest free trade areas in the world, integrating a market of 780 million people and approximately 25% of global GDP. In addition it enhanced the importance of these blocks in a global trading system marked by the prominence of the US and China. Nonetheless, internal disagreements between these blocs have threatened the ratification of the bilateral treaty. In Mercosur, Argentina and Brazil disagree regarding the reduction of import tariffs. In the EU, in turn, countries that produce agricultural goods demand more protection in relation to Mercosur. Besides that, the European Parliament’s objections to the environmental policy of the Brazilian government of Jair Bolsonaro has impeded the ratification of this treaty. Even so, South America has been the target of EU strategic cooperation. In 2019, the inauguration of EllaLink (ELLALINK, 2021), an approximately 6,000 km submarine cable system, represented the first fiber optic connection between Europe and South America that does not pass through the US. This network will leverage technological cooperation between these regions.

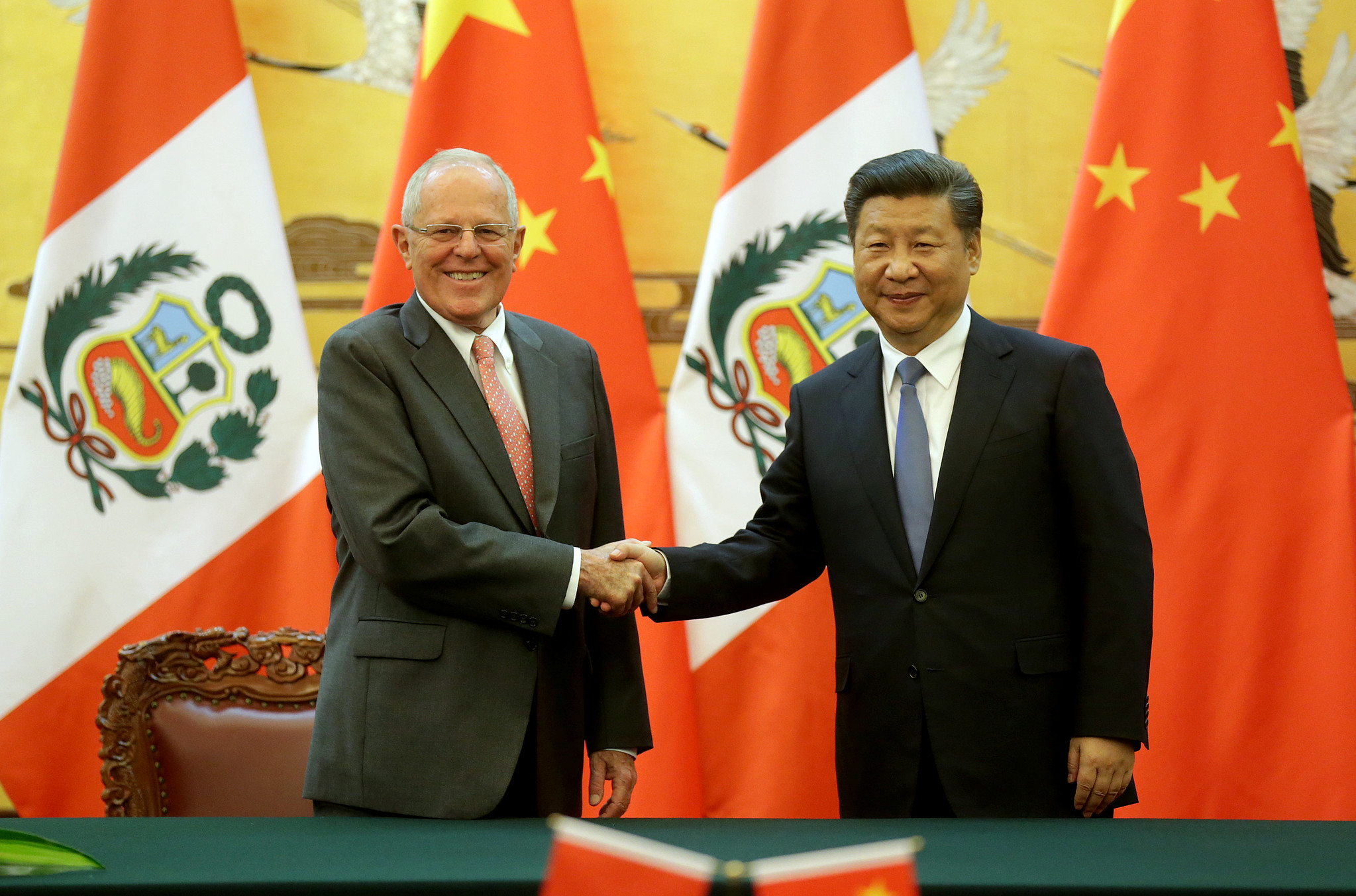

China’s rise as a global power interferes with South America’s trade and geopolitical relations. As China has shown high GDP growth rates, demand for agricultural commodities from SAC has increased. In order to protect its natural resources, the Chinese government has opted to import commodities, from other countries, notably those from South America. In this way, the trade and economic dependence between South America and China has been mutual. Just as the South American economies have become consumer markets for Chinese manufactured goods, they have also increased their dependence on commodity exports to China. In this context, China has sought to strengthen political and strategic ties with the region. In 2014, the China-CELAC Forum was created to be a platform for intergovernmental cooperation between Latin American countries and China’s foreign ministers (CHINA, 2018). Derived from this mechanism, the China-CELAC Cooperation Plan established guidelines for cooperation in various themes, such as infrastructure, environment and technology.

Brazil’s departure from CELAC in 2019 and the decline of UNASUR made China change the action pattern with South America. In the wake of UNASUR disarticulation, the Chinese government raised the possibility of incorporating the COSIPLAN portfolio into OBOR (One Belt, One Road) (FOLHA, 2018). However, just as the US had done, China began to prioritize bilateral relations with SAC. In order to guarantee access to oil reserves, the Chinese government has been purchasing large quantities of oil from Venezuela through advance payments and loan concessions. To facilitate the flow of agricultural and mineral commodities, the Chinese government presented the project for a bi-oceanic railway that will connect the western region of Brazil to the coast of Peru. Furthermore, at the II Forum of the Belt and the Route for International Cooperation, in 2017, the presidents of Chile and Argentina, tried to access Chinese financing for regional infrastructure projects (YAMEI, 2017). Moreover, in 2020, Chinese companies signed contracts worth approximately US$ 4.7 billion in order to modernize the railway network in north-central Argentina, which will reduce transportation cost for agricultural products (Ibidem, 2020). In this way, China seeks to control infrastructure networks that facilitate access to South American regional markets.

Lastly, Russia has sought to expand its global geopolitical influence. Under Vladimir Putin’s government, Moscow has been trying to regain the former Soviet Union’s international prominence. Consequently, military cooperation between Moscow and Caracas provides Russia with a SAC alliance that has privileged access to the Caribbean Sea and the Amazon rainforest (CSIS, 2020). As a result, Russia has militarily supported a government that is persistently critical of the US in a traditional area of Washington’s geopolitical influence. While the BRICS grouping has reached sectorial agreements with Brazil and the supply of military equipment to Brazil has ended, the alliance between Russia and Venezuela has proven to be more efficient for Russia’s international projection, as Moscow has been geopolitically affronting the US. In short, inasmuch as extra-regional powers pursue their own goals in South America, political fragmentation among countries in the region has intensified. At the same time, these countries are facing another disjointing process: the growing domestic political divide.

The domestic political vulnerability of South American countries

One of the main domestic consequences of the Pink Tide was the resurgence of political rivalries in SAC. Until the 2000s, conservative political groups traditionally led South American societies. Therefore, the Pink Tide was a unique event in South American political history. With the exception of Colombia, all other South American States democratically elected a leader of the political left in that decade. Although this context favored regional cooperation, which resulted in the creation of UNASUR, conservative social and political segments began to undermine the domestic stability of these governments.

The weakening of left-wing South American governments resulted from different processes. In 2002, Hugo Chávez government in Venezuela, suffered a military coup, which also dissolved the National Parliament. This coup, however, was not consolidated and was dismantled in a few days. In 2010, Ecuadorian President Rafael Correa also experienced a failed military coup attempt. In 2019, Bolivian President Evo Morales underwent a political process that resulted in his removal from office, as did Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff in 2016 and Paraguayan President Fernando Lugo in 2012. These processes were mainly based on practices of administrative irregularities.

In this context, weak economic growth, the maintenance of high socioeconomic inequality and accusations of corruption caused not only the loss of much of the support of national societies, but also the outbreak of popular protests waves. For example, the 2014 World Cup was interpreted by Brazilian society as wasted public budget, since the country has precarious public health services and poor quality transport networks. This amalgamation of collective grievances undermined the continuity of most left-wing governments in South America.

The subsequent rise to power of conservative political groups was not enough to prevent domestic processes of political fragmentation. These governments tried to eliminate political and economic initiatives of opposition governments, such as the departure from Unasur and the reduction of domestic social welfare policies. In the meantime, socioeconomic inequality, deindustrialization and the precariousness of public services, were not fully mitigated or even integrated into government agendas. As occurred in the external sphere, political groups on the right have not been able to propose alternatives that are considered effective by the society. This political weakness has led to the return to power of left wing political groups, in Argentina, Bolivia and Peru, and to cases of political radicalization. In Chile, the far right and the far left wing disputed the second round of the 2021 presidential elections, which demonstrates the disbelief of South American societies in relation to moderate political groups.

Internal divisions have fueled political rivalries in SAC. Unable to establish a consensual political agenda, these governments have suffered from recurring political and social pressures, whether from civil society or economic groups. Political polarization and fragmentation between and within countries occurs along with the disintegration of intraregional trade. Without forging basic policy guidelines, SAC become even more vulnerable to political and trade disputes between extra-regional powers.

The present and future of South American integration

Political regionalism became a secondary issue for South American Heads of State. Due to the process of trade disintegration and political fragmentation, the scope of regional interdependence is reduced. Although there are still institutions that promote sub-regional rapprochement, such as Mercosur, PROSUL Forum and the Pacific Alliance, current interdependence is not enough to leverage a political process that incorporates South America.

In the last decade, South American political geography has become more heterogeneous. Regional cooperation arising from the Pink Tide was replaced by unstable and partial political initiatives and inefficient institutional arrangements. Just as the Lima Group did not provide a political alternative to Venezuela, PROSUL did not encourage South American cooperation, nor did it propose a consistent project for regional integration. From now on, SAC must seek minimum standards of political convergence to build a political regionalism based on their current characteristics.

Consequently, the reactivation of Unasur will not be a solution to improve regional governance. Even if presidents of the political left again govern most SAC, trade disintegration and political fragmentation will not be mitigated through UNASUR activities. The regional and global political and economic panorama are very different from those that existed in the late 2000s. The development of regional cooperation mechanisms is now much more difficult than it was, since current global order presents the intensification of rivalries between powers. To overcome this disjunctive logic, the governments of SAC must consider three variables that influence political regionalism.

First, SAC must identify what the optimal level of interdependence will be for their respective national goals. This level will be fundamental for the development of regional cooperation initiatives in specific sectors. In a context of renewed mutual trust, the adoption of decision-making standards based on consensus seems to be ideal, since it does not limit the sovereign decisions of States. In this way, regional governance will have a political mechanism that can provide benefits to all SAC. For example, to deal with health crises or pandemics, the convergence of States’ efforts tends to optimize resources and achieve better results, in addition to enabling the construction of broader and more effective action plans.

Secondly, the topics that will integrate the regional integration agenda must be strategic for all SAC. As Nations have prioritized expanding their exports to extra-regional markets, the regional integration model that will be implemented must meet this objective. The construction of bi-oceanic logistic corridors is compatible with this strategy, since it can transport the production of commodities and, at the same time, stimulate the formation of regional value chains, tourism and energy integration. Therefore, the expansion of trade with other regions of the world does not impede sub-regional integration.

Third, the political will of national societies determines the existence of political regionalism. This political will derives from the interest to undertake collective actions, as long as these actions provide relative gains. Therefore, regional cooperation must be a mechanism that provides concrete initiatives to meet social, trade and political concerns. For example, the integration of transport, energy and communications infrastructure networks should result in gains in competitiveness for productive sectors and in lower prices paid by consumers. Thus, political will is stimulated by the shared benefits of regional cooperation.

If SAC manage to balance these three variables, political regionalism could once again become an important instrument to expand South America’s influence on the global scenario. The economic disintegration and political fragmentation that plague regional relations have transformed SAC into actors that only adapt to systemic changes. They lost the condition of proactive actors, which they exercised between 2000 and 2015. During this period, in addition to the creation of IIRSA and UNASUR, SAC organized several summit meetings with African, Arab and Asian countries, through the CELAC-China Forum. Since then, the two main regional economies, Argentina and Brazil, began to show increasing strategic divergences and diplomatic distance, which impaired the search for regional integration. In the last few decades, the success of regional and sub-regional cooperation and integration initiatives has derived from the political synergy between Buenos Aires and Brasília. The return to structural stability through integration is essential for the future of South America’s political regionalism.

Conclusion

Regional integration is an objective that is no longer on the political horizon of South America. This context seems incompatible with the cooperation that was established a decade ago. Just as political and institutional advances occurred in the early 2000s, they were disrupted in the second half of the 2010s. In the wake of a process of trade disintegration and increased dependence on extra-regional powers, SAC have gone through successive initiatives of political fragmentation that illustrate the lack of political convergence. The crisis in Venezuela triggered a political division between political groups on the right and left that undermined the regional cooperation that was developing within the scope of UNASUR since 2000.

UNASUR has not achieved full regional integration, but it has stimulated cooperation in specific areas. Through theme-specific councils, SAC have developed regional projects that have been relatively successful. However, these countries were unable to maintain their search for regional integration. Strongly related to the Pink Tide, this search has not withstood the rise to power of representatives of the right. Notwithstanding the creation of the Lima Group and PROSUL, regional cooperation became precarious.

The return of left-wing governments in some SAC has given rise to the resurgence of UNASUR. Strategic objectives and the relationship between SAC and extra-regional powers have changed substantially in the last few decades. Greater dependence on extra-regional powers has made regional integration a secondary objective, even if governments are ideologically convergent. Thereby, the resumption of the search for regional integration will depend on a successful overlapping of heterogeneous interests, since commercial, political and geopolitical interests are generally interdependent. More than governments with the same political orientation, SAC need joint strategies to expand the region’s international projection and regain its global relevance.

References

BARROS, Pedro Silva. Desintegração Econômica e Fragmentação Política na América do Sul, 13 de agosto de 2020. Latinoamérica 21, https://latinoamerica21.com/br/desintegracao-economica-e-fragmentacao-politica-na-america-do-sul/ , December 6, 2021.

CHINA. The 2018 China-CELAC Forum. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, March 6, 2018. Beijing, http://www.chinacelacforum.org/eng/ , December 14, 2021.

CERVO, Amado. História da Política Exterior do Brasil. Brasília: UnB, 2015.

COSTA, Carlos Eduardo; GONZÁLEZ, Manoel José. Infraestrutura e integração regional: a experiência da IIRSA na América do Sul. In: Boletim de Economia e Política Internacional. Brasília, número 18, 2014, pp. 23-40, http://repositorio.ipea.gov.br/bitstream/11058/5325/1/BEPI_n18_Infraestrutura.pdf , December 3, 2021.

COSTA, Wanderley Messias da. O Brasil e a América do Sul: cenários geopolíticos e os desafios da integração. In: Revista Confins. São Paulo: n. 7, 2009, pp. 2-23, http://www.uel.br/cce/geo/didatico/omar/brasil_america_sul.pdf , December 11, 2021.

CSIS. An Enduring Relationship – From Russia, With Love. Center for Strategic & International Studies. Washington, September 24, 2020, https://www.csis.org/blogs/post-soviet-post/enduring-relationship-russia-love , December 18, 2021.

DORATIOTO, Francisco. Maldita Guerra: nova história da Guerra do Paraguai. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2002.

DURÁN LIMA, José Elías; CRACAU, Daniel. The Pacific Alliance and its economic impact on regional trade and investment: Evaluation and perspectives. The Economic Commission for Latin America and The Caribbean. Santiago, 2016, https://www.cepal.org/fr/node/40621 , December 15, 2021.

ELLALINK. Evento da União Europeia apresenta novo cabo submarino de fibra óptica entre Brasil e Portugal. EllaLink Press Releases. Dublin, June 1, 2021, https://ella.link/2021/06/01/evento-ue-apresenta-cabo-submarino/ , December 17, 2021.

EU. The EU-Mercosur trade deal. The European Commission. Brussels, May 11, 2020, https://ec.europa.eu/trade/policy/in-focus/eu-mercosur-association-agreement/ , December 28, 2021.

_____ (b). The EU and CELAC summits. The European Commission.Brussels, February 3, 2020, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/E-9-2020-000617_EN.html , December 29, 2021.

FOLHA. De uma estação espacial na Argentina, China expande seu alcance na América Latina. Folha de São Paulo. São Paulo, July 10, 2018, https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/mundo/2018/07/de-uma-estacao-espacial-na-argentina-china-expande-seu-alcance-na-america-latina.shtml , December 13, 2021.

IIRSA. Declaration on the South American Community of Nations, the 2004 South American Presidential Summit. Initiative for the Integration of Regional Infrastructure in South America. Cusco, December 8, 2004, http://www.iirsa.org/admin_iirsa_web/Uploads/Documents/oe_cusco05_declaracion_del_cusco_eng.pdf , December 9, 2021.

_____ . Summit Meeting of the South American Presidents in 2000. Initiative for the Integration of Regional Infrastructure in South America. Buenos Aires, September 2000, https://iirsa.org/en/Page/Detail?menuItemId=41 , December 4, 2021

NATO. Relations with Colombia. North Atlantic Treaty Organization. Brussels, June 17, 2021, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_143936.htm , December 29, 2021.

PECEQUILO, Cristina; CARMO, Corival do. O Brasil e a América do Sul: relações regionais e globais. Rio de Janeiro: Alta Books Editora, 2015.

SENNES, Ricardo. Brazil in South America: Internationalization of the Economy, Selective Agreements and the Hub-and-Spokes Strategy. In: The Perspective of the World Review. Brasília, v. 2, n. 3, 2010, pp. 107-139, http://repositorio.ipea.gov.br/bitstream/11058/6349/1/PWR_v2_n3_Brasil.pdf , December 6, 2021.

US. Communiqué of Brasilia in 2000. Department of State. Washington, September 1, 2000, https://2009-2017.state.gov/p/wha/rls/70994.htm , December 7, 2021.

_____ . The US’ Major Non-NATO Ally. Embassy and Consulates in Brazil. Brasília, March 17, 2019, https://br.usembassy.gov/major-non-nato-ally/ , December 30, 2021.

VEIGA, Pedro; RIOS, Sandra. O regionalismo pós-liberal na América do Sul: origens, iniciativas e dilemas. In: Série Comércio Internacional. Santiago, n. 88, pp. 5-48, 2007, https://www.cepal.org/pt-br/publicaciones/4428-o-regionalismo-pos-liberal-america-sul-origens-iniciativas-dilemas , December 11, 2021.

WEGNER, Rubia Cristina. Integração e desenvolvimento econômico: estratégias de financiamento do investimento de infraestrutura sul-americana. In: Economia e Sociedade. Campinas, v. 27, n. 3, pp. 909-938, 2018), http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1982-3533.2018v27n3art8 , December 14, 2021.

YAMEI. Joint communique of leaders roundtable of Belt and Road forum. Xinhuanet. Beijing, May 15, 2017, http://www.xinhuanet.com//english/2017-05/15/c_136286378.htm , December 15, 2021.

Doutorando em Geografia Política. Pesquisador e colunista da Revista Relações Exteriores